Photo by Lara Ferroni

Photo by Lara Ferroni

To prepare sodium hydroxide lye for soapmaking, it needs to be dissolved in some type of liquid. The dissolved lye solution is then emulsified with oils to create soap. Distilled water is usually the liquid of choice for dissolving lye. But, some soapers prefer to use other liquids such as milk, tea or alcoholic beverages. Using alternative liquids (anything other than distilled water) in cold process soap is an intermediate to advanced soaping technique. It requires a few extra steps to prep and can affect other aspects of the soaping process.

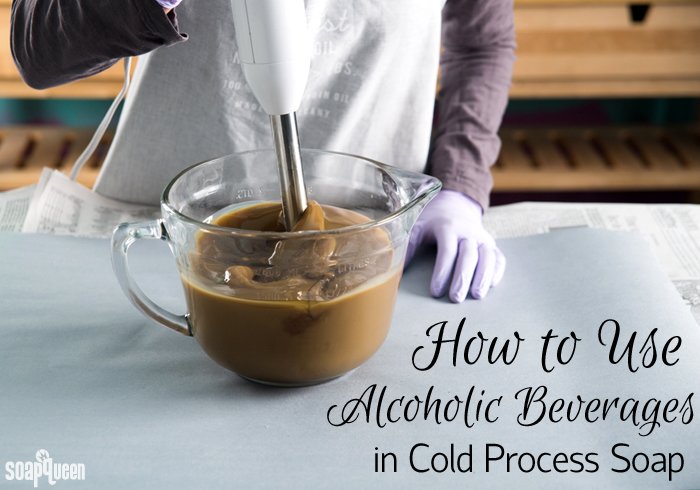

One of the most popular types of alternative liquids for cold process soap is alcoholic beverages. This includes beer, wine and champagne. These liquids contain sugar, which give the soap a stable and fluffy lather. Alcoholic beverages can also give the soap color and are great from a marketing standpoint. Some alcoholic beverages do contain beneficial properties like antioxidants, but it is debatable whether these properties make it through the saponification process.

Making soap with alcoholic beverages poses a few challenges. They contain sugar that becomes very hot when mixed with sodium hydroxide lye. This turns the liquid a deep color due to the sugars scorching and can cause an unpleasant aroma. In addition to sugar, alcoholic beverages contain...you guessed it! Alcohol. Alcohol and the saponifcation process don’t mix very well. In addition, many alcoholic beverages such as beer and champagne are carbonated. Carbonation and the saponification process don’t mix very well either.

The key to eliminating the alcohol and carbonation is to boil the liquid prior to using it for soap. This cooks off the alcohol, leaving behind a liquid that works better in cold process soap. Adding lye to alcohol or carbonated beverages can cause an eruption, so boiling the beverage is extremely important. If using a carbonated beverage, many soapers allow the beverage to go flat for several days then boil it to remove the alcohol. I’ve prepared my alcoholic liquid both ways, with similar results.

Beer, wine and champagne all contain a smaller amount of alcohol than spirits (hard liquor). In general, I don’t recommend using hard alcohol as the liquid in your soap. It can be done, but it’s a very advanced technique. There is a lot of alcohol to boil out in hard liquor, and it will cause your soap to accelerate. If you’d like to use a spirit in your soap, I recommend using a very small amount and supplementing the remaining liquor with distilled water, beer, wine or champagne.

The key to using alcoholic beverages in cold process soap is to boil the liquid first to reduce the alcohol and carbonation.

The key to using alcoholic beverages in cold process soap is to boil the liquid first to reduce the alcohol and carbonation.

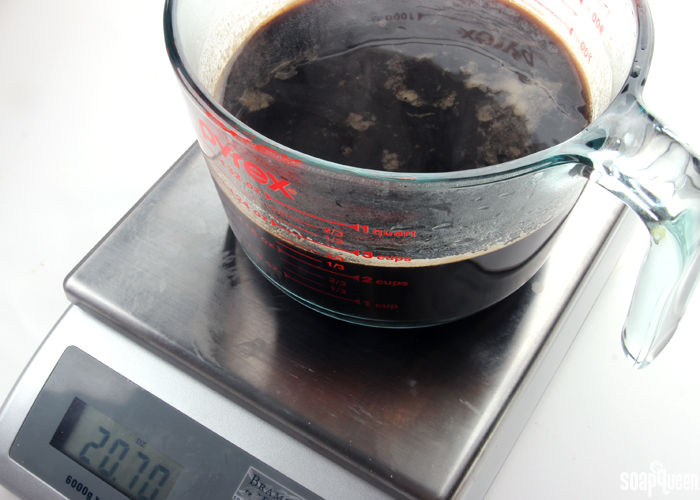

To prepare the alcoholic liquid, first weigh how much you’ll need for the total recipe. You can substitute 100% of the recipe’s liquid with beer, wine, etc., or you can substitute a portion and use distilled water for the remainder. Just keep in mind that the more alternative liquid you use, the more natural sugars it will add to your recipe. It may also give your recipe a darker colored batter, because the liquid will darken as the lye is added and the natural sugars scorch.

I always recommend boiling more liquid than you actually need in your recipe. This is because as the liquid boils, some of it evaporates and you may end up not having enough. If this happens, you can always add more distilled water to the liquid to make up for what was lost. It’s important to have enough liquid for the recipe because the liquid acts as the very important carrier for the sodium hydroxide. For example, let’s say your recipe calls for 10 ounces of liquid. To be on the safe side, I would boil about 12-14 ounces of my alcoholic beverage to account for the volume it will lose. Once it’s done boiling, eyeball the volume measurements and weigh the liquid again to make sure you have enough. If I were to weigh my liquid and only end up with 8 ounces and from the volume measurements, it was clear I was short on liquid, I could add 2 ounces of distilled water to make up for what was lost. Or, I could just use the 8 ounces and consider it a very heavy “water” discount. Click here to learn more about water discounting.

After boiling the liquid, it will be less in volume and weight. Make sure to eyeball the volume and weight the liquid after boiling to find out how much boiled-down alcohol you’re actually working with.

After boiling the liquid, it will be less in volume and weight. Make sure to eyeball the volume and weight the liquid after boiling to find out how much boiled-down alcohol you’re actually working with.

Once the alcohol has been boiled to remove the alcohol and carbonation, it needs to cool. You can place the liquid in the fridge to thoroughly chill, or you can freeze it and add the lye flakes to the frozen liquid. The colder the liquid, the less the sugars in the liquid will scorch when the lye is added. Less scorching means the liquid will not turn as dark and won’t smell quite as much. But freezing the liquid prior to adding the lye won’t prevent it from discoloring entirely. Adding the lye to the cool liquid slowly also helps keep the soap temperature down and preserves a lighter color.

In my book, Pure Soapmaking, one of the recipes uses a mixture of rose wine and champagne (see the final bars here). After the mixture is boiled to help remove alcohol and carbonation, the mixture is frozen. Then, the lye is added directly to the frozen liquid. As the lye is added to the frozen wine blend, the liquid begins to melt as the temperature increases. The increase of temperature causes the sugars to burn the liquids slightly, causing the color to change from a light pink to a deep orange (see bottom right photo). If the wine blend wasn’t frozen prior to adding the lye, the lye solution would have become much hotter, which would have resulted in a darker liquid.

Freezing alternative liquids prior to adding the lye helps prevent the liquid from burning, but won’t always prevent it entirely! Photos by Lara Ferroni.

Freezing alternative liquids prior to adding the lye helps prevent the liquid from burning, but won’t always prevent it entirely! Photos by Lara Ferroni.

After the lye is added to the liquids, allow it to cool to appropriate soaping temperatures (we like soaping around 100-130 °F). Once the solution is cool, it’s ready to use just like lye solution made with water. Keep in mind that the lye solution made with alcoholic beverages contain sugar. This will cause your trace to move quickly. When working with alternative liquids, I prefer to use a slow moving recipe with plenty of liquid oils.

Using alcoholic liquids with sugars will cause an increase in temperature. This means the soap will be more likely to go through gel phase. This is also true for soap made with honey, milk or purees. ‘Gelling’ and ‘gel phasing’ in cold process soap refers to a part of the saponification (soapmaking) process where the soap gets warm and gelatinous – up to 180 degrees. If you’d like to learn more about gel phase, click here. If you’d like your soap to go through gel phase, keep it warm but be careful to not over insulate as too much heat could cause a volcano. If you want to prevent gel phase, I recommend soaping cooler and placing the soap in the fridge or freezer for several hours up to overnight to keep temperatures cool.

Once the soap is made, soap made with alcoholic beverages still need 4 to 6 weeks of cure time. The smell of the beverage will not last through the saponification process. Using alcoholic beverages does not affect the shelf life of the soap, as all the sugars in the liquid go through the saponification process and turn into soap. The sugars will add to a stable and fluffy lather!

If you’d like to learn more about making soap with beer or other alcoholic beverages, check out the tutorials and blog posts below! In addition, making soap with alcoholic beverages is similar to making soap with other sugary liquids like milk, so you may find those blog posts helpful as well.

Bramble Beer Soap

Luck of the Green Beer (CP Tutorial)

Black and Tan Beer Soap

Advanced Oatmeal Stout CP

Guest Tutorial: Marbled Beer Soap

How to Add Lye to Milk for Cold Process Soap