Stick blenders are an amazing tool in the soapmaking world. They can emulsify oils and lye in a minute or less, while whisks and hand mixers can take hours. Have you ever had a recipe thicken a little bit too quickly? As in, instant pudding as soon as the lye is added? Don’t toss out that stick blender! You may be dealing with “false trace.”

Stick blenders are an amazing tool in the soapmaking world. They can emulsify oils and lye in a minute or less, while whisks and hand mixers can take hours. Have you ever had a recipe thicken a little bit too quickly? As in, instant pudding as soon as the lye is added? Don’t toss out that stick blender! You may be dealing with “false trace.”

Trace is the point in soapmaking when the oils and lye have started to saponify. Once the soap reaches thin trace, it will continue to thicken as you work with it. This post has more information on trace. There are two types of false trace: fake emulsification and cool soap. This blog post deals with the cool soap type of false trace. False trace looks like the soap has saponified, as it gets quite thick. However, it is actually oils like coconut or butters like cocoa in the recipe starting to harden and resolidify before the soap is fully emulsified. Below is an example of true thick trace. False trace can look and feel like thick trace, but happens very quickly after the lye and oils are combined.

False trace looks like thick trace, but the soap hasn’t fully emulsified.

False trace looks like thick trace, but the soap hasn’t fully emulsified.

What causes false trace?

Temperature is the main cause of super thick fake false trace. When cold or room temperature lye water is poured into the soapmaking oils, it can cause them to harden up. While soft oils like avocado are always liquid, hard oils are solid up to a certain temperature. For instance, avocado butter starts to melt around 90 ° F. Cocoa butter is even higher at 100 ° F. Check out the Soaping in the Summer Heat post for more information on melting points. If adding cold lye to butters and oils that are solid at cooler temperatures, it can cause the oils/butters to cool and thicken on contact.

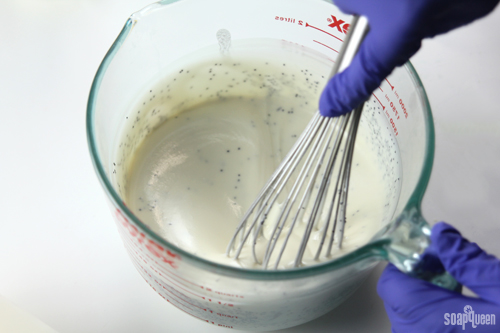

Notice the streaks of oil in the photos below? These mixtures have not reached trace, because they are not thoroughly mixed. Some of the oils have not yet started saponification, and the mixture is not completely emulsified. These mixtures need more stirring and stick blending to reach trace. If the soap was poured into the mold at this point, the soap would not properly set up. There may also be pockets of unsaponified oil and lye in your soap, which may cause skin irritation.

Notice the streaks of oil in the photos below? These mixtures have not reached trace, because they are not thoroughly mixed. Some of the oils have not yet started saponification, and the mixture is not completely emulsified. These mixtures need more stirring and stick blending to reach trace. If the soap was poured into the mold at this point, the soap would not properly set up. There may also be pockets of unsaponified oil and lye in your soap, which may cause skin irritation.

Adding poppy seeds into medium trace soap keeps them evenly suspended throughout the batter.

Adding poppy seeds into medium trace soap keeps them evenly suspended throughout the batter.