When diving into the world of soapmaking at 16, I began with the messiness of cold process soap, rendering fat, and navigating the challenges of a craft with scarce resources and zero instructions. The initial five batches were failures, leading me to explore the world of melt and pour soap, which, at the time, wasn’t as popular as it is today. Despite the hurdles, my passion for soapmaking grew, eventually leading me back to cold process soap. However, the introduction of lye, or sodium hydroxide, made the transition intimidating for many, including myself.

Understanding Lye:

Lye, a caustic chemical, indeed demands utmost respect and careful handling. Its reputation for causing bodily harm is honest, but working with lye becomes safe and manageable with proper precautions, like driving a car or operating a gas stove. For a detailed guide on lye safety, refer to the [Lye Safety Guide](insert link).

You’ve encountered lye before in products like Drano or other drain cleaners. While these products contain sodium hydroxide, they are unsuitable for soapmaking due to additional chemicals. This underscores the importance of sourcing lye from reputable suppliers, such as Bramble Berry, which is 98% pure sodium hydroxide.

Dispelling Myths:

Contrary to dramatic portrayals, lye is not the corrosive substance depicted in movies like Fight Club. The discomfort from lye exposure typically starts with an itch and mild sting, progressing to a more intense sensation with prolonged contact. However, the immediate and severe damage portrayed in movies is not the reality.

Safety First:

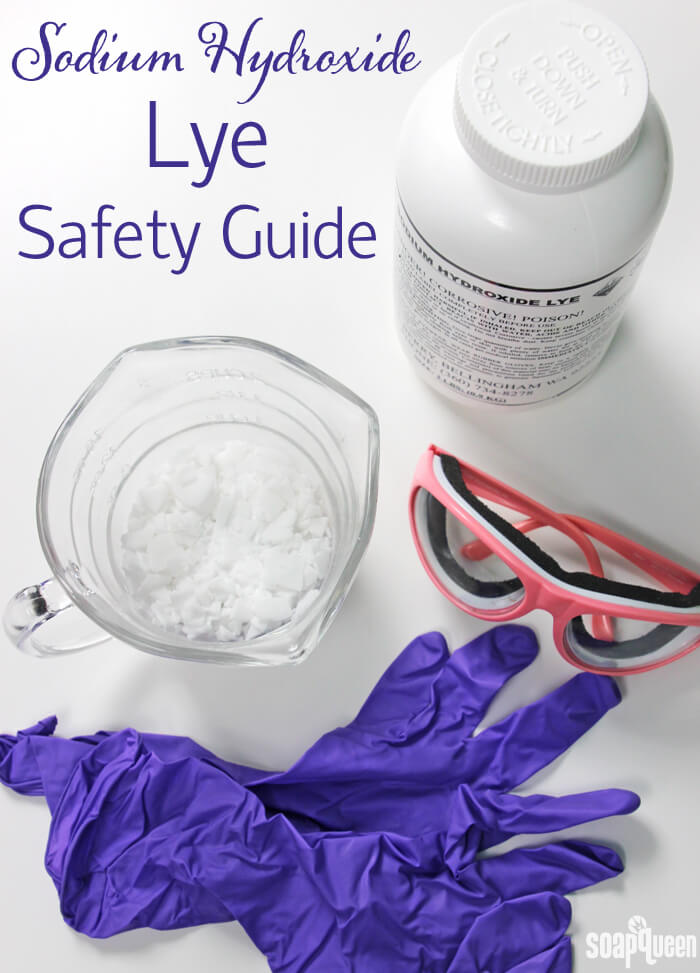

When working with lye, safety precautions are non-negotiable:

- Wear long sleeves, long pants, closed-toed shoes, protective gloves, and eye goggles.

- Cover your entire body to minimize skin exposure.

- Consider wearing a mask to avoid inhaling lye fumes, especially when mixing water and lye.

Addressing Lye Fumes:

The exothermic reaction between water and lye generates fumes, and while some soapmakers opt for masks, a well-ventilated room can often suffice. Mixing lye water outside or near open windows is a wise precaution, especially if you live in a small space.

Experienced Perspective:

After two decades of crafting cold-process soap, I can attest to never experiencing a severe lye burn. My worst encounter involved soap batter on a fresh cut, resulting in a stinging sensation that quickly subsided with proper care.

Parting Advice:

Embracing a healthy fear of lye is essential, but it shouldn’t hinder your exploration of cold process soap. Respect the seriousness of working with lye, follow safety guidelines diligently, and don’t let fear be a roadblock to your soapmaking journey.

For further insights and a visual guide to lye safety, refer to the OG Soap Queen TV video (different than the one embedded in this blog), where timeless information on lye safety is shared. Or head to the Bramble Berry Blog to learn more about Lye Safety here.

Remember, while lye demands caution, it’s a fundamental element in the alchemical artistry of soapmaking. With respect and knowledge, you can navigate this aspect of the craft safely and confidently.

Working with lye requires safety gear like

Working with lye requires safety gear like